July 20, 2016

By: Michael Feldman

A team of scientists at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands have developed a technology that uses chlorine atoms to read and write data, enabling extremely dense storage to be constructed. The prototype device can store just a single kilobyte of data, but if it was scaled up to one square centimeter, it would have a capacity of 10 terabytes.

Nature published an article on the research, which explains the technology with the help of Delft physicist Sander Otte, the lead author of the study. Otte characterized the device as “by far the largest assembly on an atomic scale that’s ever been created,” adding “it outperforms state-of-the-art hard disk drives by orders of magnitude in data capacity.”

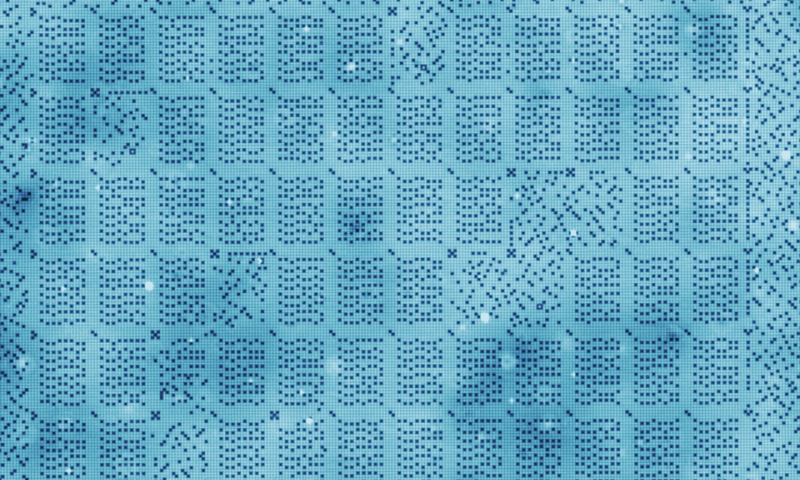

The technology is based on a rather simple set-up: chlorine atoms are arranged into square grids on a copper surface. A bit is essentially made up of two slots on the surface. The presence of a chlorine atom in one of the two slots indicates a “1,” while two empty slots indicate a “0.” The tricky part is manipulating the chlorine atoms, which is done with a scanning tunneling microscope that includes a sharp needle to probe the atoms and move them from one slot to another.

Source: Delft University of Technology

This is not exactly high bandwidth storage though. Even though the scientists have added a technique to optimize accessing the bit patterns, according to the Nature article, the process takes “a few hours to read or write.”

The other big drawback is that the device must be kept extremely cold, -196C (-321F) to be specific, which requires the use of liquid nitrogen as a coolant. As inconvenient as that is, it’s warmer and less expensive than some previous attempts at atomic storage, which relied on liquid helium as a coolant.

Setting aside the performance and cooling issues, the researchers said that if the they could scale their atomic grids into three dimensions, the storage densities would become even more attractive. According to them, a 3D configuration could provide hundreds of terabytes of data in a device the size of a grain of sand, enough to house the entire contents of the US Library of Congress.